Odds of a “hard landing” in the U.S. are rising, warns Campbell Harvey of Research Affiliates.

That’s because the Federal Reserve has this year continued battling inflation with interest-rate increases, on top of aggressive rate hikes over the past year, to compensate for being too slow to realize the surge in cost of living was not temporary, said Harvey, director of research at Research Affiliates, in a note.

In his view, the Fed’s May 3 decision to raise its benchmark rate another quarter-percentage point, along with its previous hike, “heightened the likelihood of a hard-landing recession.” The central bank will determine at its next policy meeting, scheduled for June 13-14, whether to keep lifting rates to bring down inflation.

The U.S. may be in “the lull before the storm,” said Harvey, who also is a finance professor at Duke University, in a phone interview Thursday. “Unemployment is always low before a recession.”

His view on a soft versus hard landing has recently shifted, as indicated in his note.

“In early January, even though my yield-curve indicator was flashing Code Red that a recession was imminent, I made the case that dodging the bullet was possible — the U.S. economy could avoid a hard landing,” Harvey wrote. “The wildcard was the Fed.”

Harvey pioneered the idea that an inverted yield curve is a recession indicator, with the inversion involving the yield on three-month Treasury-bills

TMUBMUSD03M,

rising above the rate on the 10-year Treasury note

TMUBMUSD10Y,

Longer-term Treasurys typically have higher yields than shorter-term U.S. government debt; the inversion of that relationship historically has predicted economic contractions.

Fed’s ‘handiwork’

“The inverted yield curve — largely the Fed’s handiwork — opened the door to two causal channels to recession,” Harvey said in his note.

The first channel is the “self-fulfilling prophesy of its successful track record as a recessionary signal,” which may prompt companies and consumers to save more and postpone investment, according to the note.

That “naturally leads to slower growth,” he wrote. “If the Fed had stopped hiking rates this year, this channel would probably have led to a soft landing or possibly no recession at all.”

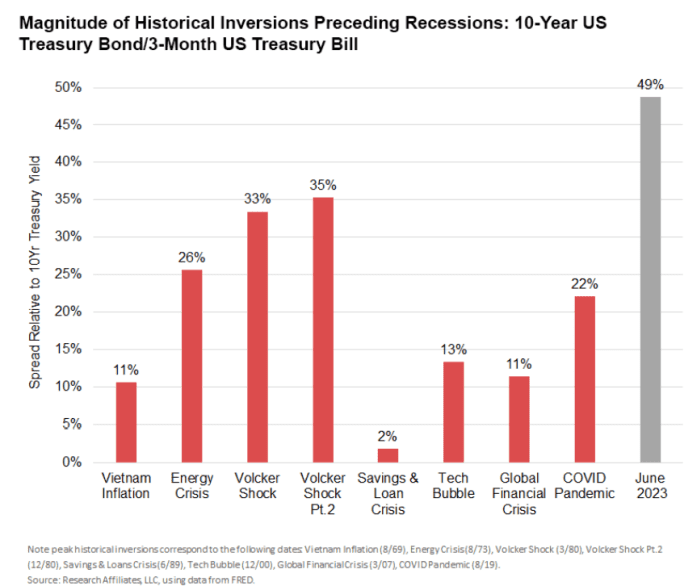

The second channel involves the magnitude of the inversion putting “major stress” on the U.S. banking and financial systems, Harvey’s note says.

“If you severely invert the yield curve, then you put the financial sector at risk,” he said by phone. “And that’s exactly what’s happening.”

RESEARCH AFFILIATES NOTE BY CAMPBELL HARVEY

“A positively sloped yield curve (long-term rates higher than short-term rates) is good for bank health, because banks generally pay short-term rates (for savings deposits) and receive longer-term rates (on their loan book and investments in longer-term government bonds),” he wrote.

“By aggressively raising short rates, the Fed has upended the normal model and created risk,” Harvey said in his note, leaving banks struggling with a mismatch in their assets and liabilities.

That is, they hold longer-duration bonds and loans that earn low interest rates, he wrote, after “banks and other institutions reached for yield” by taking on more risk as the Fed kept rates near zero even as economic growth was “robust,” stock prices were at record highs and unemployment was low. On the liabilities side, which is customer deposits, the market rate banks must pay is “much higher.”

‘Worst possible type of inversion’

“The worst possible type of inversion is where both the short rate goes up and the long rate goes up,” Harvey said by phone. “That’s what we had.”

Unloading the longer-duration bonds from banks’ portfolios to pay their depositors who want to withdraw funds is problematic because the securities are now trading at “discounted values” as a result of rates at the longer end of the yield curve rising during the Fed’s interest-rate-hiking cycle, according to Harvey.

“Liquidating these bonds to pay depositors who wish to withdraw their funds translates into bank losses,” he wrote.

The Fed began raising its benchmark rate from near zero in March 2022. The central bank’s policy rate is now at target range of 5% to 5.25%.

“The Fed’s refusal to pause rates through the first five months of 2023 sets up an unwanted scenario: a hard landing,” wrote Harvey. “Regulatory oversight and stress tests failed to identify or properly assess the duration risk that upended some of the banks.”

After Silicon Valley Bank and two other large banks failed earlier this year, the Fed found itself in “a lose–lose situation,” according to his note. Pausing rate hikes risked being seen as signaling “a fragile banking system” and potentially leading to panic, whereas “another hike would intensify stress on the financial system.”

Harvey suggested the Fed could provide “a data-driven analysis of bank risks” to alleviate uncertainty over the extent of the damage in the financial system.

“I have no idea how many banks are like zombie banks,” Harvey said by phone. “It’s very opaque.”

Meanwhile, commercial real estate is a vulnerable area that may be “the next source of stress in the economy,” he said.

“On the positive side, it does look like the Fed will not hike rates in June, but this will be six months too late,” said Harvey. “Further, a pause is not a cessation. It is widely expected the Fed will resume hikes later in the summer.”

Harvey told MarketWatch that with inflation declining from its peak, further rate hikes would be like a “self-inflicted wound” for the U.S. economy as they work with a lagging effect. “We’ve overshot already,” he said.