At this point, stock-market professionals can recite a litany of explanations for why the U.S. market has marched higher this year.

But a group of Wall Street strategists believe chalking up the equity market’s gains to signs that the U.S. economy is heading for a “soft landing,” or that the Federal Reserve could aggressively cut interest rates next year, doesn’t tell the full story.

Those who have been trawling about for a more comprehensive explanation have found their answer by closely scrutinizing the balance sheets of the world’s largest central banks, with a particular emphasis on the Fed.

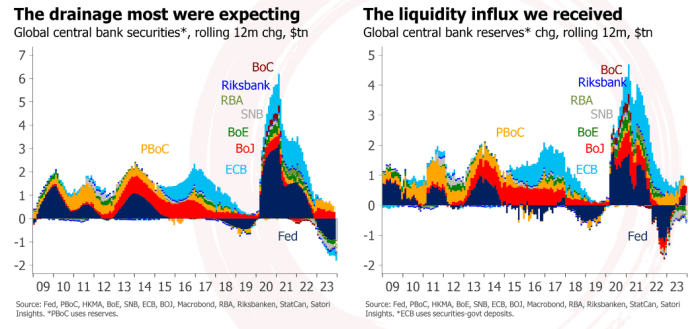

Here’s what they found: That while the Fed has been paring back the size of its balance sheet, beneath the surface, central banks have boosted support for markets by allowing bank reserves to expand, increasing the amount of capital available to be deployed into markets and the economy.

Historically, when this happens, securities prices rise, even if their advance doesn’t seem justified based on the strength of the economy, or the outlook for corporate earnings, according to research from former Citigroup strategist Matt King, who now runs Satori Insights, his own independent research shop.

“It is reserve changes that correlate best with markets. They are correlated to changes in equities and changes in credit spreads, and there is just enough of a lag that it can’t be that way round,” King told MarketWatch during a phone interview.

So how is liquidity increasing?

At first brush, this explanation might seem contradictory.

Some investors might wonder how the Fed can simultaneously inject more liquidity into the financial system while reducing the size of its balance sheet.

But according to King, the fact that the Fed has reduced its bondholdings to $7.8 trillion, from $9 trillion at its peak last year, isn’t what investors should be focusing on.

Instead of the Fed’s shrinking balance sheet, what really matters is how reserves in the U.S. banking system have increased by $500 billion since January, according to King.

The Fed isn’t alone in this. Instead of withdrawing $1 trillion in liquidity after declaring war on inflation in 2022, the world’s biggest central banks instead injected roughly an equivalent amount, King’s research shows.

SATORI INSIGHTS

Rising bank reserves are being driven by a number of factors, including the continuing drain of the Fed’s reverse-repo facility. Counterparties have removed more than $1 trillion from the facility since April, according to Fed data.

SATORI INSIGHTS

The wave of liquidity support for markets began late last year, around the time the S&P 500 bottomed in October 2022. Initially, it was driven by the Bank of Japan, People’s Bank of China and European Central Bank, King said.

Then the Fed joined the party in earnest in the spring, when it moved to support the U.S. banking system following the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. More recently, the drain of money out of the Fed’s reverse-repo facility has been the main driver.

Wall Street takes notice

King is hardly alone in taking a close look at liquidity. Recently, top strategists at Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs Group and other investment banks have discussed the impact that the RRP drain and money flowing out of the Treasury General Account has had on markets.

“The first 10 days of December continued the recent trends of expanding U.S. liquidity, driven by draws from the RRP facility and the Treasury General Account,” said a team of cross-asset analysts at Goldman Sachs in a recent report obtained by MarketWatch.

“Together with the lagged-behind effects from the U.S. policy impulse easing in the aftermath of the regional-bank funding pressures earlier in the year, the high liquidity should support risk-asset performance and tight credit spreads into year-end,” the Goldman team added.

By Goldman’s count, banking reserves expanded by roughly $50 billion on net during the first week of December alone.

GOLDMAN SACHS

Strategists at the investment bank expect this trend should continue to support stocks through January, until the Treasury releases its next update on its plans for issuing bonds and Treasury bills, which could impact the reverse-repo facility. The facility has already seen more than $1 trillion depart since April, according to the Fed’s data.

‘QE-like’ returns

If the liquidity impulse fades, stocks could run into trouble, King said.

But whatever happens early next year, King hopes to convey that if the market’s rebound in 2023 seemed “QE-like” — a reference to the Fed’s postcrisis and postpandemic bond-buying programs — then there is a reason for that.

U.S. stock indexes have now erased all of their losses from last year, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average

DJIA

finishing Wednesday at a fresh record north of 37,000.

The S&P 500

SPX

has gained 22.6% through Wednesday’s close to 4,707.09, its highest closing level since January 2022.

Meanwhile, the tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite

COMP

is up more than 40% year to date.

“There is a reason why QE is so powerful,” King said. “QE creates new money in the form of reserves, but not only that, it withdraws bonds and bills from the market, so the private sector then has more money, and fewer places to invest that money.”

“When reserves change, that alters the balance between how much money private investors have got, and the amount of securities available to invest in,” he said.

“When you give investors less money, and more securities to invest in, then we see prices go down. Reserves were coming down in 2022 when everything was selling off. But this year, that has stopped.”