Speculation that the 60-40 portfolio may have outlived its usefulness has been rife on Wall Street after two years of lackluster performance.

But as the yield on the 10-year Treasury note

BX:TMUBMUSD10Y

hovers around 4%, some strategists say the case for allocating a healthy portion of one’s portfolio to bonds hasn’t been this compelling in a long time.

And with the Federal Reserve penciling three interest-rate cuts next year, investors who seize the opportunity to buy more bonds at current levels could reap rewards for years to come, as waning inflation helps to normalize the relationship between stocks and bonds, restoring bonds’ status as a helpful portfolio hedge during tumultuous times, market strategists and portfolio managers told MarketWatch.

Add to this is the notion that equity valuations are looking stretched after a stock-market rebound that took many on Wall Street by surprise, and the case for diversification grows even stronger, according to Michael Lebowitz, a portfolio manager at RIA Advisors, who told MarketWatch he has recently increased his allocation to bonds.

“The biggest difference between 2024 and years past is you can earn 4% on a Treasury bond, which isn’t that far off from the projected return in U.S. stocks right now,” Lebowitz said. “We’re adding bonds to our portfolio because we think yields are going to continue to come down over the next three to six months.”

Does 60-40 still make sense?

Since modern portfolio theory was first developed in the early 1950s, the 60-40 portfolio has been a staple of financial advisers’ advice to their clients.

The notion that investors should favor diversified portfolios of stocks and bonds is based on a simple principle: bonds’ steady cash flows and tendency to appreciate when stocks are sliding makes them a useful offset for short-term losses in an equity portfolio, helping to mitigate the risks for investors saving for retirement.

However, market performance since the financial crisis has slowly undermined this notion. The bond-buying programs launched by the Fed and other central banks following the 2008 financial crisis caused bond prices to appreciate, while driving yields to rock-bottom levels, muting total returns relative to stocks.

At the same time, the flood of easy money helped drive a decadelong equity bull market that began in 2009 and didn’t end until the advent of COVID-19 in early 2020, FactSet data show.

More recently, bonds failed to offset losses in stocks in 2022. And in 2023, U.S. equity benchmarks such as the S&P 500

SPX

have still outperformed U.S. bond-market benchmarks, despite bonds offering their most attractive yields in years, according to Dow Jones Market Data.

The Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Total Return Index

AGG

has returned 4.6% year-to-date, according to Dow Jones data, compared with a more than 25% return for the S&P 500 when dividends are included.

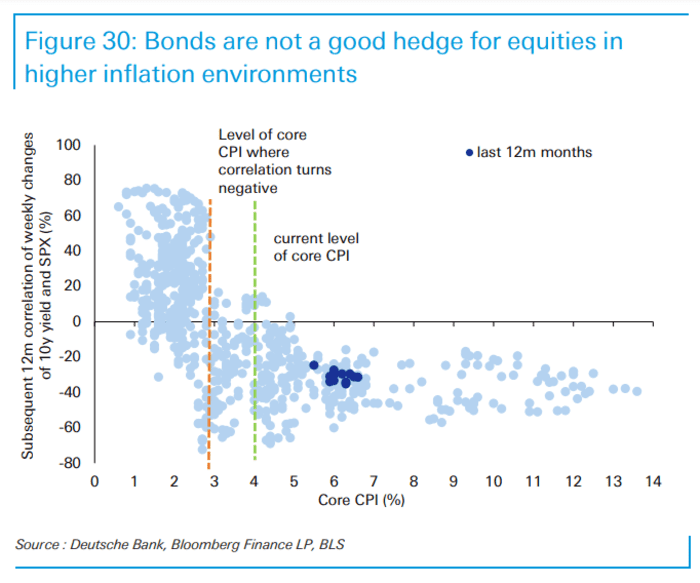

But this could be about to change, according to analysts at Deutsche Bank. The team found that, going back decades, the relationship between stocks and bonds has tended to normalize once inflation has slowed to an annual rate of 3% based on the CPI Index.

DEUTSCHE BANK

The CPI Index for November had core inflation running at 4% year over year, a level it has been stuck at for the past several months. The Fed’s projections have inflation continuing to wane in 2024.

Staff economists at the central bank expect the core PCE Price Index, which the Fed prefers to the CPI gauge, to slow to 2.4% by the end of next year. If that comes to pass, investors should see the inverse relationship between stocks and bonds return, according to Lebowitz and others.

A window of opportunity

The dismal performance of 60-40 portfolios over the past two years has inspired a wave of Wall Street think pieces questioning whether it still makes sense for contemporary investors.

A team of academics led by Aizhan Anarkulova at Emory University in November presented findings showing that over a lifetime, investors would have reaped higher returns via a portfolio consisting of 100% exposure to stocks, split between foreign and domestic markets.

But fixed-income strategists at Deutsche and Goldman Sachs Group, as well as others on Wall Street, say investors wouldn’t be well-served by excluding bonds from their portfolio, particularly with yields at current levels.

Rob Haworth, senior investment strategy director at U.S. Bank’s wealth-management business, says investors now have an opportunity to lock in attractive returns for decades to come, ensuring that the bonds in their portfolios will, at the very least, deliver a steady stream of income that would reduce any losses in stocks or declines in bond prices.

There is, however, one catch: with the Fed expected to cut interest rates, that window could quickly close.

“The problem is, for investors in cash, the Fed’s just told you that is not going to last. I think that means it is time to start thinking about your long-term plan,” Haworth said.

Read: Fed could be the Grinch who ‘stole’ cash earning 5%. What a Powell pivot means for investors.