Dear Quentin,

I’ve read your advice to other people. I’ve suffered for a long time with my own financial and family problems. I would value your thoughts.

My younger brother developed a lifelong drug addiction when he was a teenager. My father, who grew up in an orphanage, provided him with financial support that enabled him to, as my brother once said, have a home and family while “being too drugged to ever see them clearly.”

He saw his whole world through a haze. He also said that getting off drugs was difficult enough, but because our parents were financially supporting his addiction, life became impossible for him. My father purchased some things for my brother, including a house and cars, but kept them in his name so my brother could not sell them.

But my father also created opportunities for my brother to steal from him. Sometimes he would send my brother to collect thousands of dollars from a customer, and the money would of course go missing.

“‘My father created opportunities for my brother to steal from him. Sometimes he would send my brother to collect thousands of dollars from a customer, and the money would go missing.’”

Another time he sent my brother to his house, where he had left several bank passbooks on a counter. These situations let my father claim that he had been robbed by my brother and that he was not giving my brother money to buy drugs.

This went on for decades. I often had nightmares that my brother needed me to rescue him, but I couldn’t figure out how to do it. Of course, I pleaded with my father many times. I even had thoughts of harming him to free my brother.

Once I called the district attorney’s office and begged for help, but I was told that no crime was being committed.

Question 1: What else could I have done?

After my father died, my mother continued this practice, with excuses like this one: “He calls me for money. He says it’s for medical bills or to pay gambling debts.” She told me, “I can’t say no to him.”

She distributed almost all of my father’s estate to his children. I used my own share and other savings to take advantage of a really good real-estate opportunity. I have a small pension and have lived very modestly for 5 to 10 years.

“‘Eight years after my father passed away, my mother asked me to return the money she gave me from my father’s estate. Of course, she really wanted the money for my brother.’”

Eight years after my father passed away, my mother asked me to return the money she had given me from my father’s estate. Of course, she really wanted the money for my brother. She said that she was at the end of her life and didn’t want to die penniless. I told her that I needed time to sell the land.

She became very angry with me, saying that I had enough money to live on and I should give her those funds. I explained that I had enough liquid assets to live off of for a few years, but that if I was to pay her back immediately, I would have to try to sell my real estate during the 2008 financial crisis.

I was in good health, close to 70 years old. I was planning to sell the property when the market recovered and use the funds to live on for the next couple of decades. Liquidating my investment in 2008 would have put me in poverty for the rest of my life.

My mother was always a very frugal woman, and even at an advanced age her intellect and personality had not changed. She would never imagine wanting to die holding a large amount of cash. It had to be my brother’s idea.

“‘My mother enlisted my sister and my son to help her. We all agreed that it was her money and I should return it. But they all felt I should give her the money immediately.’”

My mother enlisted my sister and my son to help her. We all agreed that it was her money and I should return it. But they all felt I should give her the money immediately, and that after that, my finances would be my problem.

Whether she wanted the money for herself or my brother didn’t matter to them. I felt that after holding the money for eight years, I should be given some time to liquidate the property efficiently, which I did. My mother remained angry with me for the remaining two years of her life.

Over the years, my brother frequently called me asking for money. I always told him I loved him, then turned him down. Once I agreed to meet him, but instead I took him to a good rehab center. He always appreciated me and told me he loved me. Not being able to help him was the curse of my life.

Question 2: What, if anything, should I have done differently regarding my mother’s request?

For years, my mother took her three children out to dinner at least once a year. After the main course, my mother would always order cake, ice cream or pie for my brother, who also had diabetes. He never asked for it, nor did he refuse it.

I’d get angry with my mother and protest that my brother had severe diabetes, which was already destroying the nerves in his feet. She, being obese herself, would respond that nobody had put me in charge of his diet and that he deserved some sweets just like the rest of us.

I always let it end like that until one dinner after my mother had died. I was visiting my hometown, and my sister and her husband invited my brother and me to dinner at their favorite new restaurant.

I was surprised that she invited my brother, but I was happy to see him. During the dinner she took charge of the ordering, even requesting a very expensive wine, thus making it clear that we were her guests, and she was paying for the evening.

“‘After the main course my mother would always order cake, ice cream or pie for my diabetic brother. He never asked for it, nor did he refuse it. I’d get angry with my mother and protest.’”

After the main course, she ordered dessert for herself and for my brother. I wanted to object again, but knowing that my objections didn’t matter when my mother was alive, I thought they probably still wouldn’t matter now that my sister was taking over.

Besides, the people who think it’s a good idea to give cake to a very sick diabetic person aren’t going to listen to what I have to say. So I yanked the plate of cake away from my brother. My sister became enraged. The whole family descended on me in a rage: “You come for a visit and think you’re taking over? He can decide for himself!”

Question 3: What should I have done at the dinner?

All I could say in my defense was that he’s my little brother, he’s sick and I need to protect him. In the days to come, my daughter and other family members all unanimously agreed that I was an evil, controlling person.

Only one person came up to me, hugged me, told me he loved me, and thanked me: my brother.

Sincerely,

A Brother and Son Who Tried to do the Right Thing

Dear Brother,

Let me answer your questions in reverse order.

You did what you did. When you’re dealing with a family member who has had a substance-misuse disorder for most of his life, and your family has chosen to enable, ignore or finance his addiction. You do not need to be forgiven for intervening. This was an act of frustration and pain decades in the making. We are all human. Your family’s history of acquiescence may go back not years, but generations.

Snatching the plate away was a minor infraction of dinner-party etiquette. Their response was totally out of proportion. Your family did not see red because you yanked away a plate with a piece of pie on it; they lost the plot because you addressed the elephant in the room — not your brother’s diabetes, but his long history of addiction and your family’s willingness to turn a blind eye to it.

Your brother has two diseases: addiction and diabetes. Your family’s creed was built on sweet desserts and secrets. You had the courage and the tenacity to unmask that. Your father enabled your brother, perhaps because he himself had not been given the tools to address the problem. Your mother stood by and then asked for your inheritance back to ensure your brother had enough money to live on.

Your sister, for better or for worse, is your mother’s daughter. She grew up with the same lessons: that the best thing to do was to ignore your brother’s addiction. Nobody in your family had the knowledge or capacity or, perhaps more accurately, the willingness to address this problem. Your sister played along, and she showed her love and support the only way she was taught to do.

“‘Your family did not see red because you yanked away a plate with a piece of pie on it. They lost the plot because you directly addressed the elephant in the room.’”

You have been held hostage by your brother’s disease and by your family’s unwritten rules and values. You found a rehab facility. But he had to want to get better, and he was the only one who could do it. You tried time and again. The dessert was the last straw. It’s never best to act out of frustration, but you did shine a big neon sign on decades of silence and facilitation. You broke their rules.

Regarding Question 2: You ask what else you could have done in response to your mother’s request. Of course, you could have said no. It was your money. But as your brother’s relationship with the rest of your family shows, this is not a family built on people saying “no” to others. It is a family based on “yes.” But always saying “yes” does not leave room for your own happiness. You did the best you could at the time.

As to Question 3: What else could you have done to protect your father from your brother? Your father may have felt under pressure to help your brother financially, but he was not under your brother’s care, and you do not cite any signs of emotional abuse, aside from the financial needs of a person who was in the throes of the disease of addiction and, perhaps, did not have a steady income.

You could have staged a family intervention, but you would have needed the cooperation of your/his family, or your brother’s friends. You did find a rehab facility for your brother, but he also needs to stay the course and want to get sober. You can’t live other people’s lives for them, and it’s a mistake to punish yourself for not doing enough for someone who could not or would not help themselves.

“You can use phrases like, ‘I will support you if you take this path.’ You are letting him know that you care about him, you want to help him, and you will be behind him 100% if he seeks the path of recovery. ”

No one thanked you for selling the land. Instead, your mother was angry that you did not do it on her terms — and, lest we forget, her anger helped persuade you to hand over the money. You stood by your brother, a man who acknowledged that one person at that dinner table was strong enough and bold enough to set a boundary in order to protect him. Forgive yourself for doing the best you could do.

You loved your brother, and you protested at how you believe your family enabled him. They acted as a tribe that does things their way. Your brother took drugs and he ate sweet desserts. Your family was beholden to his addiction and tied to the ways they have always done things. You attempted to break those rules. I’m not sure even Mahatma Gandhi could have succeeded where you did not.

We are all a product of our upbringing. The 12-step program Al-Anon has a very simple message for family members of people who have drug and alcohol problems — family members who have spent their lives putting other people first: “You didn’t create it, you’re not responsible for it and you can’t cure it.” But you can be there to offer your help, and let your brother know that you will support his recovery.

You can use phrases like, “I will support you if you take this path.” You are letting him know that you care about him, you want to help him, and you will be behind him 100% if he seeks the path of recovery. But you are making it clear that you do not support his ongoing misuse of substances. In the absence of a family intervention, continue to encourage your brother to seek treatment.

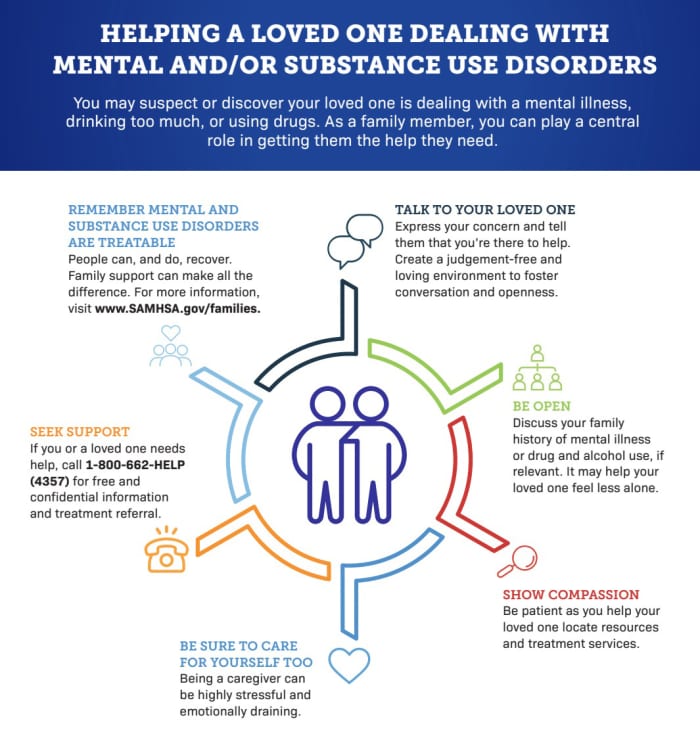

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, a branch of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, aims to help families dealing with addiction issues. It offers advice on how to start a conversation with a loved one: “1. Identify an appropriate time and place. 2. Express concerns, and be direct. 3. Acknowledge their feelings and listen. 4. Offer to help. 5. Be patient.”

If you, or a family member, needs help with a mental or substance use disorder, call SAMHSA’s National Helpline at 1-800-662-HELP (4357) or TTY: 1-800-487-4889, or text your zip code to 435748 (HELP4U), or use SAMHSA’s Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator to get help. You can also find more resources and advice for families from SAMHSA here.

Here are other resources for people with family members who have addiction issues: The Center for Motivation and Change published this book, “Beyond Addiction: How Science and Kindness Help People Change.” Dr. Robert Meyers, who has been working in the field of addiction for four decades, developed the CRAFT approach to encourage a family member to engage in treatment.

Source: SAMHSA

You can email The Moneyist with any financial and ethical questions related to coronavirus at qfottrell@marketwatch.com, and follow Quentin Fottrell on Twitter.

Check out the Moneyist private Facebook group, where we look for answers to life’s thorniest money issues. Readers write in to me with all sorts of dilemmas. Post your questions, tell me what you want to know more about, or weigh in on the latest Moneyist columns.

The Moneyist regrets he cannot reply to questions individually.

More from Quentin Fottrell: